Menu

The Diversity of Domestic Abuse: How to be Inclusive when Supporting Staff

Simon was 21 years old when he met his girlfriend, and their relationship quickly became serious; the pair had moved in together in a matter of weeks. Eighteen months later, Simon lost his life to this same girl, who his family and work later discovered had been abusing him physically, emotionally, and financially for the entire duration of their relationship. Yet, due to the attached stigma of a man being abused by a woman, Simon did not seek help – and because many external bodies, such as his workplace, have only been trained to spot signs of domestic abuse in women, no one was able to direct Simon to the help he needed.

Simon’s workplace, like all companies, have a responsibility to offer support and guidance when they are led to believe or made aware of a member of staff who is experiencing domestic abuse. Whether it be physical, psychological or a mix of both, managers should be trained on how to respond to these appropriately.

However, many organizations are failing to address the intersectionality of domestic abuse through their support strategies.

For one thing, lockdown brought with it a significant spike in domestic violence reports, with MSI Reproductive Choices finding a 33% increase. Refuge also released new figures which found that calls to their domestic abuse helpline had increased during lockdown by 61%. Despite leaving the pandemic behind, the hybrid and remote working models are more popular than ever, and so the increased proximity risk for domestic abuse to occur is still very much present.

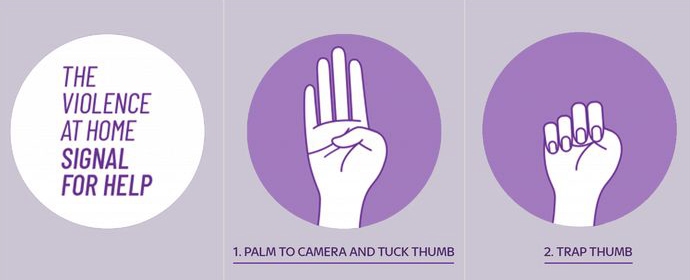

Employers must begin to look at ways of updating their support strategies to keep up with these changing working environments. One way that businesses can start to do this is by training staff to be aware of a Violence at Home Signal for Help. This would be teaching a covert hand signal that can be made over a video call to make their colleagues aware that they are in danger but are unable to verbally say so.

But this is only the first step. Companies need to start shifting their perception of domestic abuse as being something that only affects heterosexual women. Most strategies will be tailored to the experiences of straight women, as this is the group of people who statistically suffer the most. But a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach can mean employers fail to recognise and respond to those who fall into different groups.

According to the Crime Survey of England and Wales, 27.6% of women have experienced domestic abuse behaviors compared with 13.8% of men. However, many men do not report domestic abuse due to perceived embarrassment and the reluctance to even admit to themselves that they are victims. As a result, the number of men suffering could be much higher.

Similarly, the experiences of people from the LGBTQ+ community will vary significantly from those of straight men and women with around 25% of LGBTQ+ people suffering violent or threatening relationships.

For those in queer relationships, there are a number of unique attributes in the way they are abused. For example, some people are threatened with having their sexual orientation ‘outed’ to people who they have not shared it with. As well as this, many queer people will believe their sexuality or gender identity is the reason why they are being abused, which fuels feelings of internalised homo/bi/transphobia.

Employers must continue to educate themselves around the diversity of domestic abuse. Knowing how it can affect different people, as well as being able to recognise the varying signs, will allow the company to be able to support their employees promptly, and avoid tragic cases like Simon’s.

Those suffering can have noticeable issues in performance, as well as higher absenteeism, which eventually leads to reduced productivity and lower output. And just because domestic abuse is something that happens in the home, does not mean it won’t follow people into the office – up to 75% of employed victims are harassed by their abusers while at work, through repeated calls and texts and visits to the workplace.

Businesses that begin updating their strategies will be able to help those that are suffering, as well as mitigate the effects that domestic violence can have on work performance. Fostering a culture of openness will make it easier for staff to approach leaders with these issues. And when approached, it is important to avoid gendered language when asking questions – substitute ‘boyfriend/girlfriend’ for ‘your partner’ – so to avoid making someone potentially uncomfortable.

Organizations should also be able to direct men and LGBTQ+ people to appropriate helplines. Men’s Advice Line is dedicated to helping male victims, while GALOP provides a national LGBTQ+ domestic abuse helpline.

If you need guidance on how to develop your domestic abuse strategies, please get in touch with me at therese@orgshakers.com

Copyright OrgShakers: The global HR consultancy for workplace transformation founded by David Fairhurst in 2020